In 2018, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the United Nations’ global maritime regulator, adopted mandatory measures to reduce international shipping emissions by half in 2050 compared with 2008 levels. It’s already a difficult hill to climb in to find the technical solutions for implementation, let alone determine the financial and strategic advantages of adoption without clear regulatory guidance and global support for the effort.

The US just signaled that half the emissions by 2050 wasn’t enough, with the US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry announcing the IMO should push for zero emissions by the same 2050 deadline.

It’s all in line with the Biden administration bringing the US back into the Paris Agreement. It’s a positive step in the global movement of emissions reductions, but it is likely to cause friction among certain IMO members in Asian and South American nations over the fear of rising export costs and an unequal burden among trading partners. These talks could begin at an IMO meeting as early as June of this year.

What’s The Big Deal?

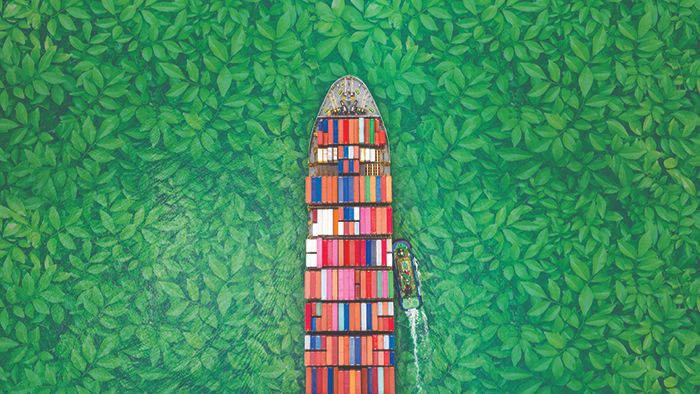

The shipping industry is one of the biggest carbon emitters on the planet. It is responsible for more than 2% of all global emissions. If the shipping industry were a country, it would rank as the sixth biggest polluter in terms of annual output. That’s more CO2 than all of Germany.

According to the IMO, global freight traffic has increased in volume by 101% in the past 20 years. Emissions have risen by 40% in the same time period.

Due to the massive size of the ships and ever-increasing efficiency, shipping has the lowest rate of emissions as a mode of transport in the supply chain.: A large vessel emits just over 1% of the CO2 ejected by the aircraft when measuring per tonne per km. Rail emits seven times and road trucks 16 times more than ships.

There are efforts u{“type”:”block”,”srcClientIds”:[“0804b2aa-10bb-4e86-8c41-9491eb5685bc”],”srcRootClientId”:””}nderway that could dramatically improve efficiency.

Which Green Fuel Should We Use?

A.P. Møller-Maersk has identified three primary candidates to replace traditional fossil fuels on the road to global maritime shipping’s decarbonization: methanol (e-methanol and bio-methanol), alcohol-lignin blends, and ammonia. Although ‘green’, many of these alternative fuels currently require energy-intensive processes to produce at scale, making them not so carbon neutral. For now.

Methanol fuel is a biofuel used in combination with gasoline or independently. Methanol is less expensive to sustainably produce than ethanol fuel, although it is generally more toxic – it breaks down into formaldehyde – and has a lower energy density.

Embalming fluids aside, methanol seems to have taken the early lead in carbon-neutral fuel, with Maersk announcing last month that its first carbon-neutral vessel will be deployed in 2023 – that’s seven years ahead of schedule. It will be a dual-fuel vessel able to run on green methanol.

Alcohol-Lignin Blends are structural biopolymers that contribute to the rigidity of plants. Lignin is isolated in large quantities as a byproduct of lignocellulosic ethanol and pulp and paper mills. It’s already used/incinerated to produce steam and electricity.

Maersk and partner companies are exploring LEO, a blend of lignin and ethanol, as a viable fuel for the future of sustainable shipping.

Ammonia is a renewable fuel made from the sun, air, and water. ‘Green’ ammonia is made by reacting nitrogen separated from air with hydrogen made by wind- or solar-powered water electrolysis.

Maersk has signed on to build Europe’s largest production facility of carbon dioxide (CO2)-free green ammonia. Ammonia is a carbon-neutral alternative the carrier has identified along with methanol as maritime’s fuel of the future. This green ammonia will be used by the shipping industry as CO2-free green fuel and Copenhagen’s agriculture sector as CO2-free green fertilizer.

Did You Say Steak?

Some South American nations fear that the cost to export meat products, fresh produce, and commodities could double if ships have to run on non-fossil fuels, which can cost roughly ten times more than conventional bunker oil.

A lot of these concerns were brought up when the IMO’s Low Sulfur Fuel rules began to be enforced in 2020, even though they had over a decade to prepare for it. Since then, the industry seems to have navigated the new regulatory regime with no major disruption, but regulatory uncertainty has held back investment in new vessels. There is concern about what class of ships will be carbon-efficient enough to profitably operate against the cost of penalties for not meeting changing standards. A new container ship’s specifications are a long-term bet on the cost of burning bunker fuel.

Lower emissions aren’t just being demanded by the UN and IMO. It’s coming from consumers who hold corporations accountable for the carbon footprint of their supply chain. Environmental responsible freight is a major selling point and #goodbranding.

It Will Cost More To Establish Green Fuel As The Norm

Once one of the alternatives is chosen as the default fuel, costs will likely fall. Shipping groups like Maersk spend more than US$4B a year on fuel. To go carbon-free right now would cost double that amount. Covering those extra costs would mean the price shipping groups charge their own customers would need to increase by around 20%. That increase in fees would ultimately be passed on to the customer. According to Maersk, that would equate to roughly a 6¢ increase to a pair of sneakers.

Shipping rates have surged amid the coronavirus pandemic. Maersk’s profits in 2020 were up 44%, earning more than US$8.2bn, and profitability for carriers is looking even better in 2021. Those profits are already being invested in research and development in technologies that will act to reduce emissions, so at least some of the cash generated from back-breaking rates are going to a worthy cause.

Innovation Costs Money. Duh

For one thing, consumers all over the world love to brag about a new, guilt-free green product they bought. It’s also incredibly helpful to – you know – stop us from polluting and cooking our planet.

And size doesn’t always matter. French inland shipowner, Compagnie Fluvial de Transport (CFT), plans to deploy the world’s first commercial cargo transport vessel powered by hydrogen. The vessel will move goods along Paris’s river Seine with another to be deployed in Norway.

It’s actually kind of a big deal. These cargo vessels will demonstrate how operating on green hydrogen can decarbonize urban rivers, translating technological innovations into commercial operations, making zero-emissions inland vessels a reality in every European city.

Sharknado… Sort Of, But Not Really

It’s not just ocean shipping that is looking to reduce emissions. Airfreight emits at the highest level of CO2 of all shipping methods. Luckily, some companies are thinking outside the box and finding results in biomimicry.

Next year, Lufthansa Cargo will cover its fleet of Boeing 777 freighters with a high-tech ‘shark skin’ coating to reduce aerodynamic drag and fuel consumption. Bringing some of the seas to the skies is proving profitable. According to Lufthansa, the sharkskin coating on 10 of its 777s will save about 3,700 tons of jet fuel and nearly 11,700 tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually— that’s equivalent to 48 individual freighter flights from Frankfurt to Shanghai.

The sharkskin coating is just one of several steps Lufthansa’s cargo division is taking to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Woo!

Change Is Inevitable

The Biden administration will push IMO to achieve its carbon goals. It may be overambitious, but it’s necessary. The shipping industry is being held accountable for its global emissions, and it is changing its ways to reduce them. All this change may cause a few waves along the way, but CargoTrans has an expert and experienced team to answer any questions or concerns you may have. All you need to do is contact us with a carbon offset email or phone call.